The article dates from March 2024. So here are two small updates:

The key issues paper on the law against digital violence has now become a draft bill, which was presented in December 2024. However, the draft was not submitted to the Bundestag before the last federal election. You can find more information here.

The population survey “Living Conditions, Safety, and Stress in Everyday Life” conducted by the BMFSFJ, BMI, and BKA was completed in January 2025. A report on the survey is expected to be published this year. We are eagerly awaiting it!

The information and surveys I found during my research mostly rely on the binary gender categories of men and women. Wherever possible, I aim to reflect the full spectrum of gender identities by using the term women (with an asterisk), referring to all individuals who do not identify as cis-male.

Maybe you’ve also seen the recent campaign by HateAid over the past few days? It aims to raise awareness of people’s rights in digital spaces.

HateAid’s latest campaign draws attention to one of the core issues the non-profit organization focuses on: digital violence.

Until the end of December, I personally associated the term—if I thought about it at all—mostly with so-called hate speech, in other words: dehumanizing language aimed at devaluing individuals or groups (source).

That changed when I watched Anne Roth’s talk at the most recent Chaos Communication Congress (37c3). Her presentation opened my eyes to the many dimensions that digital violence can take.

The German Federal Association of Women’s Counseling Centers and Rape Crisis Centers (bff) defines digital violence as follows:

Digital violence encompasses a wide range of attacks aimed at degrading, defaming, socially isolating, or coercing/extorting certain behaviors from those affected. The anonymity enabled by digital media and the broad spectrum of digital communication methods facilitate such attacks. However, digital violence also occurs within so-called close social environments (e.g., partners, friends, family).

bff Frauen gegen Gewalt e.V.

In addition to hate speech—which is only one part, not a synonym, of digital violence—examples include stalking, fake accounts, manipulation of smart devices or images, upskirting, and identity theft. In short: anything that digital technologies make possible, whether in online or offline spaces.

Examples and explanations of these forms of abuse can be found, for instance, in the brochure "Digitale Welten – Digitale Medien – Digitale Gewalt" published by the Frankfurt Rape Crisis Center and the bff (Federal Association of Women’s Counseling Centers and Rape Crisis Centers).

According to a representative survey commissioned by HateAid, around 50% of respondents aged 18 to 35 report having experienced digital violence. Many participants also state that, due to these experiences, they now hold back their opinions online.

The counseling center against sexual violence in Bonn describes the psychological effects of digital violence as comparable to those of physical or analog violence—with the added burden that it is harder to control and takes place in a much larger, often public, space (source).

When people are pushed out of digital spaces, or withdraw from them entirely, their freedom of expression is limited. And that means a basic democratic right is being restricted.

The psychological effects and the silencing of voices in digital spaces clearly show that—despite all its opportunities—ongoing digitalization also brings complex challenges.

So, what does the government say?

Short answer: not a whole lot. At least not enough.

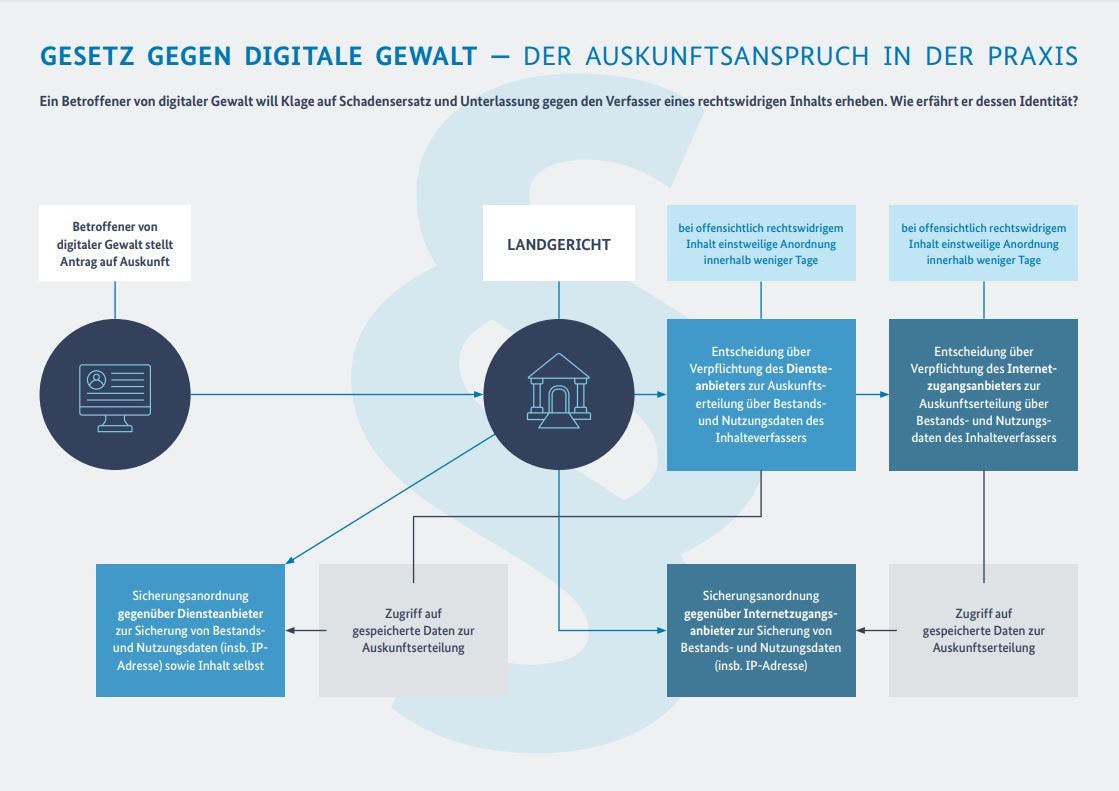

At present, the German Federal Ministry of Justice (BMJ) has published only a set of key points for a potential law on digital violence. But "key points" are not even a draft bill—and even these fall far short of effectively addressing the many forms digital violence can take.

The two biggest weaknesses:

The BMJ defines digital violence primarily as online insults.

Sure, that’s part of the problem—and an important one. But as outlined above, it’s only one aspect and doesn't do justice to the full scope of the issue.Once again, the focus is on real-name obligations and digital identification.

A tired and misguided approach. Online anonymity is a cornerstone of democracy and essential for protecting freedom of speech.

A Glimmer of Hope: A study titled “Life Situation, Safety and Daily Burdens” by the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (BMFSFJ) is expected to provide more numbers and facts on the subject in 2025. Perhaps it can at least lead to a more precise definition and greater visibility. A look at the Federal Budget 2024, however, raises the question whether there is even enough money to tackle this issue properly. Not quite 3% of the budget goes to the BMFSFJ, whose responsibilities are very extensive. It would therefore be desirable to allocate more funding to get reliable data and solution approaches, and to financially support counselling centers.

Why is digital violence also described as gender‑based violence?

According to the aforementioned HateAid survey, 30% of men and 27.5% of women report being affected by digital violence. The definition of digital violence from bff that I quoted above goes on to say:

“… As gender‑based violence, it is frequently part of (ex‑)partnership violence, stalking, and separation.” — bff Frauen gegen Gewalt e.V.

Gender‑based violence is defined by the German Institute for Human Rights as “violence directed against a person because of their biological or social gender.” (source). The Federal Office for Family and Civil Society Tasks similarly counts digital violence as part of partnership violence. Thus, digital violence is seen as an extension and continuation of partner violence, which, according to crime statistics, mainly affects women*. Many women* report that the partner violence also took place in the digital realm. There are many reports of how women* are gender‑specifically affected by digital violence — for example through cameras in festival toilets or other public restrooms.

Unfortunately, there are no reliable numbers specifically about digital violence and about who is affected how, because studies are lacking. In my research I mainly found positions stating that women* are the main sufferers of digital violence. This may be because digital violence, like analog violence, has different effects on marginalized groups — e.g. people who are affected by sexism, racism, ableism, etc. As Francesca Schmidt rightly emphasizes in Netzpolitik, the differentiation of who is affected by digital violence must be intersectional, not based solely on gender.

If we take hate speech as an example: Francesca Schmidt describes how marginalized groups are insulted in sexist and racist ways in political discussions. Rather than engaging with the person on factual issues, their gender, origin, and other factors are brought in and used to smear them. The violence becomes personal and aims to attack body and soul, not just opinion or political stance.

In the specialist documentation Digital Violence — Science, Practice, and Strategies, Dr. Nivedita Prasad and Felicia Ewert also use the term digitization of gender‑based violence. This is a somewhat different approach: not seeing digital violence per se as gender‑based, but looking specifically at violence against women* (and other marginalized groups) in the digital realm.

One way or another, as already became clear in the article on ethics and digitalization: sexism, racism, transphobia, ableism, and other forms of discrimination from the analog world continue into the digital space. Also here I am keen to see the results of the BMFSFJ study.

What can we do?

Preventively, there is little we can do to stop someone from slipping an AirTag under us or filming us in a restroom with a hidden mini‑camera. But we can support those affected—and take them seriously. We can offer our technical know‑how and share knowledge. Raise awareness of potential harms that technology can enable, which are not always immediately obvious—AirTags, mini‑cameras, spyware, etc.

The Haecksen, a FINTA‑inclusive group from the hacker scene, provide education about digital violence at antistalking.haecksen.org and also offer concrete technical instructions. Here, those affected can learn how to block a phone number or configure location services on their smartphone.

It is of course very important not to leave responsibility solely with those who are or may be harmed, and to allow no space for perpetrators. We must not risk that affected people withdraw completely from the digital space out of fear of being hurt again. Also, as always: politics and justice should move away from treating a real‑name requirement as the only solution. We should support civil society organizations that deal with the causes and effects of digital violence. Political parties can, for example through petitions like those from HateAid, be made aware that digital violence must be addressed and combatted in all its complexity, and that funds should be provided exactly for that.